Print

Print ![]() Comments Off on Tax Implications of Executive Pay: What Boards Need to Know

Comments Off on Tax Implications of Executive Pay: What Boards Need to Know  Print

Print ![]() E-Mail Tweet

E-Mail Tweet

Paula Loop is Leader of the Governance Insights Center at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP and Arthur H. Kohn is a partner at Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP. This post is based on a co-publication from PwC and Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP.

Tax issues—how pay is taxed, when, and whether that tax can be deferred—can be a key driver in designing executive pay packages.

The potential tax impacts of executive pay decisions, both for the company and for the executive, can affect how executive compensation is structured. Here, we explain the key tax issues that compensation committees should understand in order to design effective executive compensation programs.

Imagine your company’s leadership is in transition, and after an exhaustive search, the board has found the perfect CEO candidate. Next up: negotiating the employment agreement. The parties will need to agree generally on the dollar figures at play, but just as importantly, how will it be paid? How much in cash? How much in equity? What kind of equity—options, restricted stock, restricted stock units? What will the vesting conditions look like? Can any of the payments be deferred?

While it is important to consider what the pay package looks like to shareholders and to proxy advisory firms, the final decisions will also be driven by tax implications—both for the executives receiving the compensation, and for the company. In this post, we highlight some of the key tax issues that influence these decisions, as well as the design of any executive compensation program. Understanding the tax impacts will empower compensation committees to make better, smarter decisions for the company and its executives.

Quick key to tax code references

Topic

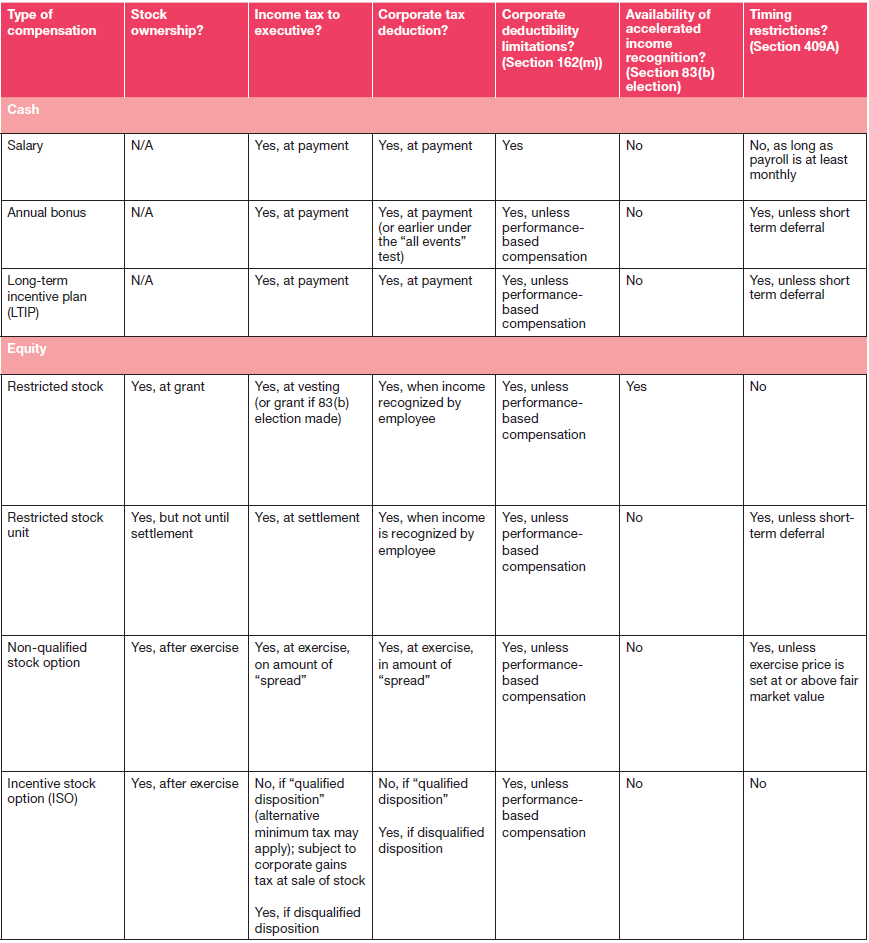

Companies strive for the perfect mix of cash and equity in their executive pay packages—the pay mix that provides enough current income to attract and retain key talent while ensuring they have “skin in the game” through equity compensation. But how do tax implications affect the question of whether to pay an executive in cash or in equity, and what forms of equity to offer?

Cash payments could be in the form of salary, annual bonus, or long-term incentives such as a multi-year long-term incentive plan (LTIP). Executives are taxed on receipt of cash payments, and the company receives a corresponding corporate tax deduction—subject to a significant limitation. Section 162(m) of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) limits the company’s deduction for compensation paid to certain executives to only $1 million, unless that compensation is “performance based”.

The company usually takes its corporate tax deduction in the same year that the executive recognizes the income. However, some companies take advantage of a special rule—called the “all events” test—that allows them to accelerate the deduction for payments such as annual bonuses. Under the all events test, the amount can be deducted in the performance year, rather than the payment year, if it is already vested and guaranteed as of the end of the performance year, and is paid out during the first 2 ½ months of the following year.

How do companies take advantage of the “all events” test when they don’t typically guarantee bonus payments until the actual payment date? The test can also be met by committing to pay a set overall bonus pool. That overall amount is deducted in the performance year, and then the compensation committee can determine the actual bonus amounts for each employee participating in the pool closer to the time of payment.

One key decision is whether to offer full-value awards, such as restricted stock or restricted stock units (RSUs), where the executive receives the full value of the stock upon vesting, or awards such as stock options that pay only the increase in the share price over a period of time.

Each form of equity has advantages and disadvantages. Stock options may focus executives more keenly on increasing shareholder value, but they also present dilution issues and could encourage risk-taking. Full value awards pay off even if stock values have declined, but they mitigate dilution concerns, since a company must offer an executive many more options (compared to full-value awards) to deliver the same value to an executive. Added to this mix of pros and cons are important tax consequences that vary across the different types of equity.

Restricted stock is stock that will be forfeited if pre-set conditions are not met. These vesting conditions are typically service-based, requiring the executive to remain employed for a period of time, but can be (and frequently are) performance-based.

The executive is the owner of the shares as of the date of grant, and therefore has the voting and other rights of a shareholder. But since the stock may be forfeited, its value is not taxable to the executive until the conditions are met and it vests.

Restricted stock offers executives the ability to file a “Section 83(b) election,” where the tax event for the company and the executive happens on the date of grant, instead of when the stock vests. It is clear why a company might prefer to take the tax deduction for the payments sooner, but why would an executive want to accelerate his or her taxes?

By making the election, the executive immediately “starts the clock” for long-term capital gains when the stock is eventually sold, and pays taxes at ordinary income rates based on the stock value at the time of the grant rather than at the later (and likely higher) value at the time of the vesting.

But the election is risky because the executive pays tax earlier than he or she otherwise has to, and pays that tax on amounts that could later be forfeited if the restricted stock doesn’t vest. Once paid, there is no refund on the tax.

As a result, Section 83(b) elections on restricted stock are more commonly made at start-up companies when the grant date value of the stock would be small and the tax impact minimal.

An RSU is a stock award that does not involve the upfront transfer of stock. Instead, the company makes a promise to the executive to deliver stock if specified vesting conditions, either time- or performance-based, are met. Unlike restricted stock, RSUs can be structured to pay out in cash, rather than in shares, which may make them more appealing for companies concerned with shareholder dilution issues.

The executive’s income tax is delayed for as long as the transfer of stock (or cash) is delayed. Typically, shares underlying RSUs transfer immediately at vesting, but in some cases they can be delivered at a later time. Unlike restricted stock, however, the deferral of RSUs may be subject to the strict rules of IRC Section 409A relating to the deferral of income.

Stock options can take one of two forms: qualified or non-qualified. “Qualified” or “incentive” stock options (also known as “ISOs”) offer special tax benefits to employees, but can only be offered in very limited amounts and give rise to alternative minimum tax issues.

ISOs avoid ordinary income tax at regular rates if they are held for a minimum period of time after grant and after exercise. The executive owes only long-term capital gains tax on gains above the exercise price when the stock is eventually sold. ISOs also escape social security taxes on exercise, regardless of when the sale occurs. However, ISOs give rise to alternative minimum taxable income at the time of exercise. If the stock value falls during the minimum holding period, the executive can owe taxes that far exceed the actual gains.

Any option that is not an incentive stock option is considered a “non-qualified” stock option.

With non-qualified stock options, the difference between (1) the value of the stock at exercise and (2) the exercise price (the “spread”) is subject to ordinary income and social security/Medicare tax when the option is exercised.

Given the tax benefits offered by ISOs, why are they so rarely used? First, they present alternative minimum tax risks. Second, the value that can be offered is subject to strict limitations—no more than $100,000 may vest in any year. Third, the fact that the executive avoids income tax also means that the company forfeits any corresponding tax deduction.

So when granting ISOs, it is important that the compensation committee balance the benefit to the executive with the loss of the company’s tax deduction, keep an eye on the value limits, and weigh the alternative minimum tax risk.

Executive pay often follows trends. Currently, companies are favoring awards with performance-based vesting, such as RSUs or restricted stock, over stock options. Why? Shareholders and proxy advisory firms tend to view these awards as more closely tying pay to company performance. Stock options usually vest over time and are valuable only if the stock price goes up. This reflects just one element of company performance—its stock price. RSUs and restricted stock also reflect the value of the stock, since they are worth more if the stock price rises. But by incorporating performance-based vesting conditions, the company can also tie the compensation to other important goals, such as achievement of specific financial metrics or individualized leadership goals.

Boards, shareholders, and proxy advisory firms alike can usually agree that a substantial portion of an executive’s pay package should be subject to some type of vesting provisions. In addition to pay for performance concerns, tax implications—and in particular the application of the deductibility limitations of Section 162(m)—can also be a driving factor in determining how those vesting conditions are crafted.

The tax code generally allows companies to deduct compensation expenses that are “ordinary and necessary.” However, the tax code imposes a strict $1 million annual limit on the amount of compensation paid to “covered employees” that may be deducted by a public company. “Covered employees” whose compensation is subject to the limitation are defined as the CEO and the next three most highly compensated executive officers, other than the CFO. Because of a lasting quirk in the tax rules, the CFO is typically not subject to the Section 162(m) limitations.

Section 162(m) was enacted in 1992 in an attempt to keep down executive pay. How effective has it been? According to a study by Equilar and the Associated Press, average CEO pay at S&P 500 companies that year was $3.7 million. For 2016, the figure is $10.8 million. How are companies getting around the limitation? They are not simply foregoing the deduction on this additional compensation. Rather, they structure it as performance-based compensation that is exempt from the limit. While tying pay to performance may seem like a positive change, some question whether it also encourages the granting of stock options, which may have led to excessive risk-taking on the part of executives who were trying to boost short-term stock price for personal reasons.

Compensation committee requirements

Plan requirements

To qualify for the performance-based compensation exemption, the amounts must be paid “solely” upon achievement of the established performance conditions. So, for example, severance arrangements cannot include automatic payment of the target amount, since in that case the payment is made regardless of whether the performance condition is achieved.

The compensation committee also may not make changes to the goals that would increase the amount of the payout, unless those adjustments are identified in advance. And the committee cannot use discretion to increase the amount of the payments.

| Vesting Condition | Performance-based Compensation? |

|---|---|

| Vests upon five years of continuous service as CEO | No, not performance-based |

| Vests if the company generates at least $1 of revenue | No, usually not substantially uncertain |

| Vests if the executive demonstrates outstanding leadership | No, not objective criteria |

| Vests if the company meets revenue target of $100 million | Yes |

| Vests if the company is profitable | Yes, profit is always considered substantially uncertain, even for a historically profitable company |

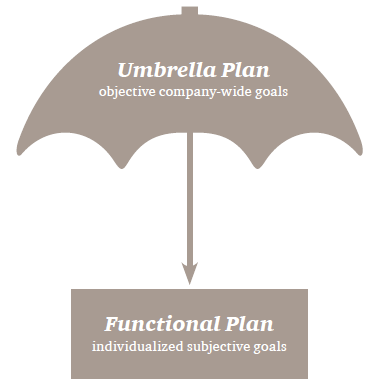

While the committee cannot use discretion to increase amounts under a Section 162(m) plan, it can decide to decrease those amounts. To take advantage of this ability to use negative discretion, some companies use an “umbrella plan” (also called a “plan within a plan”). The compensation committee or shareholders set an objective performance goal under a Section 162(m) plan that qualifies as substantially uncertain, but is considered likely to be achieved.

Separate and apart from this umbrella plan, the compensation committee creates a second set of performance goals. These goals act as the functional plan for the company. The goals need not meet the Section 162(m) requirements of being objective, performance-based, and pre-established. They may reflect more challenging financial goals, or non-objective metrics such as qualitative evaluations of performance.

At the end of the performance period, the umbrella plan generates a bonus figure based on the objective goals. The compensation committee then uses its negative discretion to adjust that amount to the right level, given the executive’s performance under the functional plan. In this way, the compensation committee retains discretion, and is able to consider the goals it determines are most relevant, while also complying with the tax code’s design requirements so that the bonus is fully deductible under Section 162(m).

Umbrella plans can provide compensation committees with useful tools to grant the appropriately-sized bonuses that are also deductible under Section 162(m), but they also may require some additional disclosure in the proxy statement to explain how the committee determined the right number. With increasing focus on pay for performance and shareholders’ push for rigorous plan goals, shareholders and proxy advisory firms alike are looking closely at performance target disclosure, and are asking for more disclosure on how bonus amounts are determined.

Tax deferred is tax saved. Deferring compensation, and the taxes that come along with it, provides an inherent financial benefit to an executive. This benefit is even greater if the taxes are deferred until a time when the executive is in a lower tax bracket. However, compensation committees should carefully weigh the value of an executive’s tax deferral against the impact to the company of a deferred compensation deduction—which could also be to a year with lower tax rates.

Compensation can be deferred in a number of forms, including:

Deferring compensation is a complicated endeavor, thanks to legislation passed following the Enron scandal. In Enron, executives were initially able to pull money out of deferred compensation plans when the company began failing, while rank and file employees were not.

The rules passed in reaction to the Enron scandal in Section 409A of the IRC are sweeping and govern how and when virtually any payment may be made to an employee or other service provider such as a director.

Common exceptions to section 409A include:

Section 409A applies to all “deferred compensation” unless a specific exception is available. Each of the exceptions is subject to certain requirements.

Many common payments are set up to comply with the “short term deferral” exception, including annual bonuses, long-term incentives and RSUs. This deferral is permitted if the payment is made in the “short term”—within 2 ½ months of the end of the year in which it vests. During the first quarter of every year, determining the prior year’s bonuses should be a top priority for compensation committees, so as not to miss the deadline.

If the pay cannot be set up to meet this or another exception, it must comply with the requirements of Section 409A, or the executive will face severe tax penalties. This generally means fixing how and when the compensation will be paid prior to the time it is earned—and not making changes. A compensation committee considering changes to existing programs, or going through contract renegotiations with an executive, should understand what types of payments can be changed or accelerated without violating the rules. Section 409A also imposes a waiting period on most executives, requiring that deferred compensation payments usually cannot be paid within the first six months after termination.

Although the company is likely the party drafting the compensation arrangements, the tax penalties for a Section 409A violation—in an unusual twist—fall solely on the employee.

Penalties for 409A violations:

Given that the company is largely tasked with drafting compensation arrangements but the penalty for a 409A violation falls solely on the employee, executives and their advisors frequently argue that they should be “grossed up” for any violations. However, in recent years shareholders and proxy advisory firms have taken a negative view of all tax gross-ups, with proxy advisory firm ISS even terming it a “problematic pay practice.” As gross-ups have fallen out of favor, executives’ lawyers are even keener to make sure the company gets it right.

In addition to the strategic and economic considerations, a change in control of the company also brings with it a unique set of tax issues related to executive compensation. These tax issues can be significant and are often baked into the structure of the deal—so compensation committees should be discussing them with advisors early on in the process, before it’s too late to make changes.

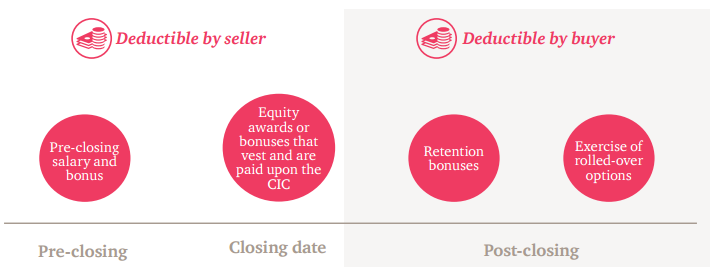

The first tax question for directors to consider upon a change in control is: which company takes the compensation deduction?

The rules surrounding this area are complex and sometimes compensation becomes entirely non-deductible and is instead required to be capitalized. Compensation committees should evaluate each element of compensation to be paid in connection with a deal, and understand whether the buyer or the seller will receive the deduction, as it could impact the overall value of the transaction.

The tax implications of so-called “golden parachutes”—payments made to executives in the context of a change in control—affect both the executives and the company. These tax implications can play a significant role in the one-on-one negotiations with executives at a target company, as well as affecting overall deal negotiations and determinations as to the final sale price.

Section 280G targets “parachute payments,” which are defined as any covered payments made to shareholders, officers or other highly compensated individuals that equal or exceed three times the person’s average compensation for the previous

five years. The tax penalties for paying any parachute payments are steep: the company loses the compensation deduction and the individual is subject to a 20% excise tax on not only the excess portion, but on all amounts above one times the average compensation.

It was once common practice to offer executives a gross-up for any excise taxes imposed as a result of a change in control. Since the proxy advisory firms and institutional shareholders have adopted a strongly negative view of gross-ups, these provisions have largely fallen by the wayside.

Every executive pay decision that a compensation committee makes will have tax effects on both the company and the executive. Understanding the tax effects makes the decision-making process both faster and more effective.